Ananya was known in her family as “the sensible one.”

She remembered birthdays, checked in on relatives, mediated arguments between her parents, and instinctively made sure everyone was okay before turning toward herself.

By 24, her body already knew the feeling: when something went wrong, it was her job to fix it. No one asked her but she learned.

No one explicitly asked her to do this but she simply learned early in her life that it was her job to fix it, mediate and make sure everything is peaceful.

Growing up in a South Asian household, Ananya internalised certain truths early. Elders came first, and their word carried authority. Emotions were handled privately and sadness was often seen as weakness, while anger surfaced only in moments of open conflict. Love was expressed less through words and more through duty, sacrifice, and dependability. “We scold you because we love you” was far more familiar than “I love you.”

So naturally, when her mother felt overwhelmed, Ananya became helpful.

When her father was stressed, she became quieter to not make him angry.

And whenever conflict arose, she stepped into the role of peacemaker.

From the outside, she appeared mature beyond her years.

But inside, her nervous system rarely fully rested.

How your ‘Caretaker Part’ Takes Shape

In my clinical practice as an IFS therapist who has worked with many south asian clients over the years , I noticed this pattern takes over time and again. People arrive exhausted or numb, and somewhere in the story is a quiet sentence that often goes unnoticed: “I feel responsible for everyone.”

Not as a role they chose, but as an identity they grew into.

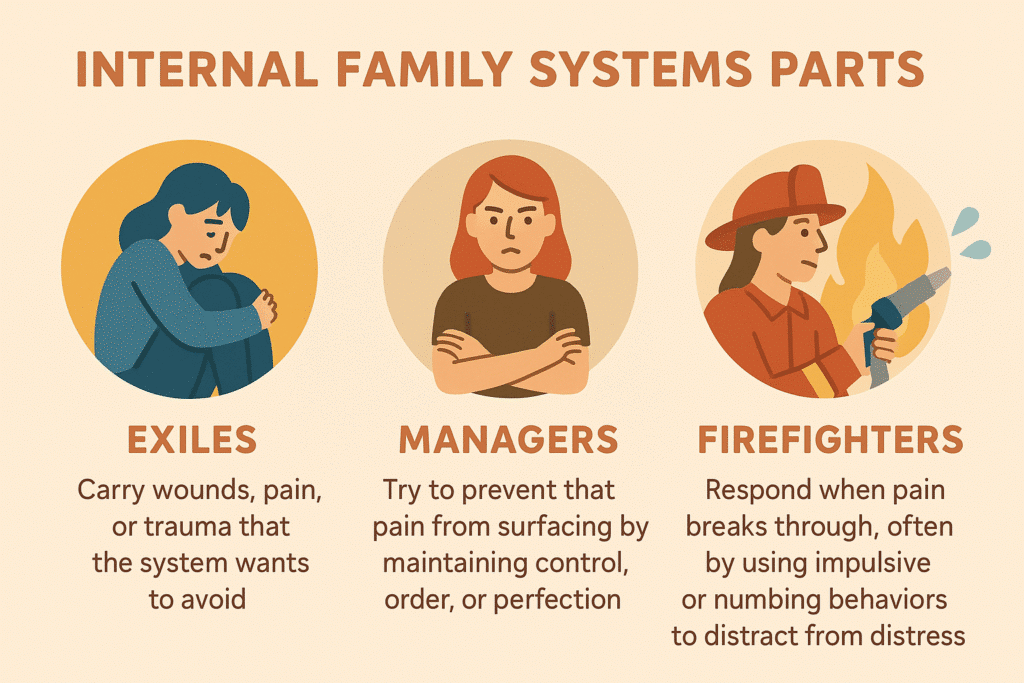

If we understand this from the Internal Family Systems perspective, these experiences are often shaped by what we call caretaker parts. IFS call them “managers” or protector parts, who take on this role when the system needs stability. Not because something is wrong. They emerge because the system needs stability.

In many South Asian families shaped by collectivism, hierarchy, and duty, children learn that emotional responsibility is part of belonging. Someone needs to anticipate needs. Someone needs to keep things from escalating. Someone needs to hold it together.

And the expression is subtle. Children learn to read tone, body language, and silence. Over time, caretaker part(s) often become hypervigilant. They learn to constantly scan the environment for emotional shifts, tension, or unspoken clues staying a step ahead to prevent conflict or distress.

Very often, this lands on eldest children and daughters. Thus completes the pattern of parentification in South Asian families. Something that is rarely named but deeply felt.

And this is adaptation, or a survival skill. But it surely doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with you!

For a long time, Ananya didn’t question this and started liking the feeling of “being needed”.

She thought this was simply who she was. Someone who cared deeply, who could handle things & who didn’t fall apart.

But…the cost started to show up quietly.

She felt tired even when she hadn’t done much physically. Rest made her uneasy. Saying no brought guilt. There was a constant hum of anxiety in her body, as if she were always waiting for something to go wrong. And sometimes, she felt resentful toward the very people she loved most.

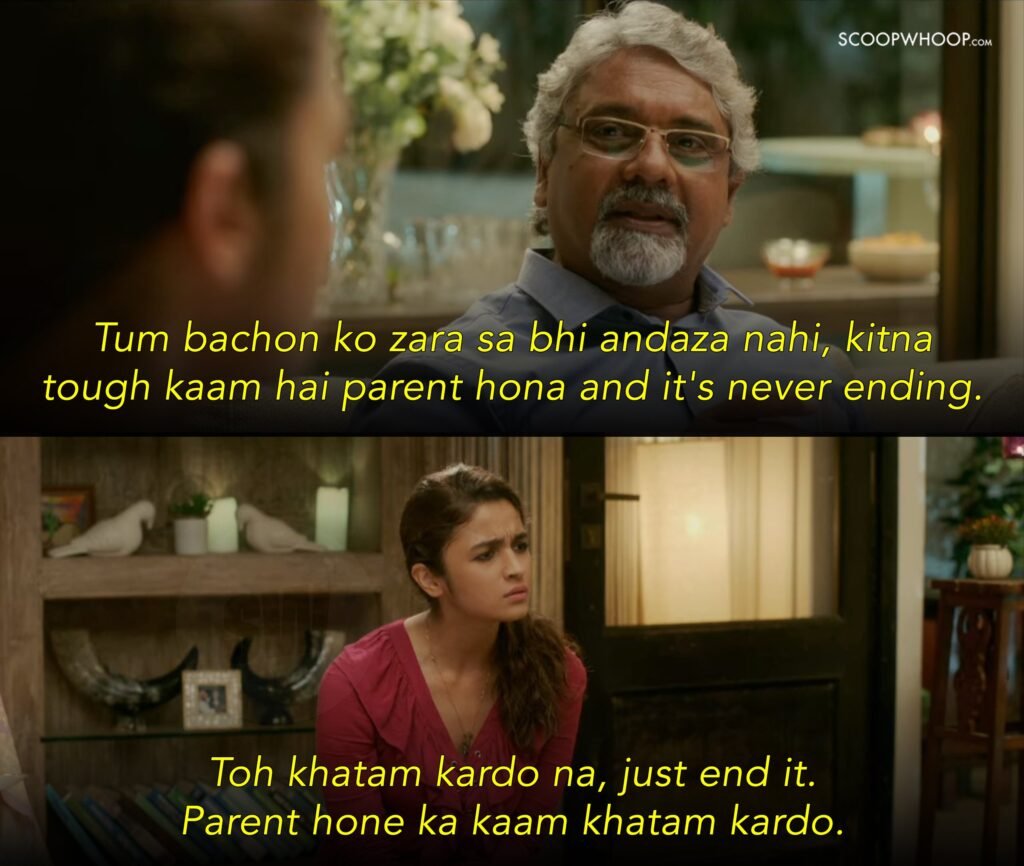

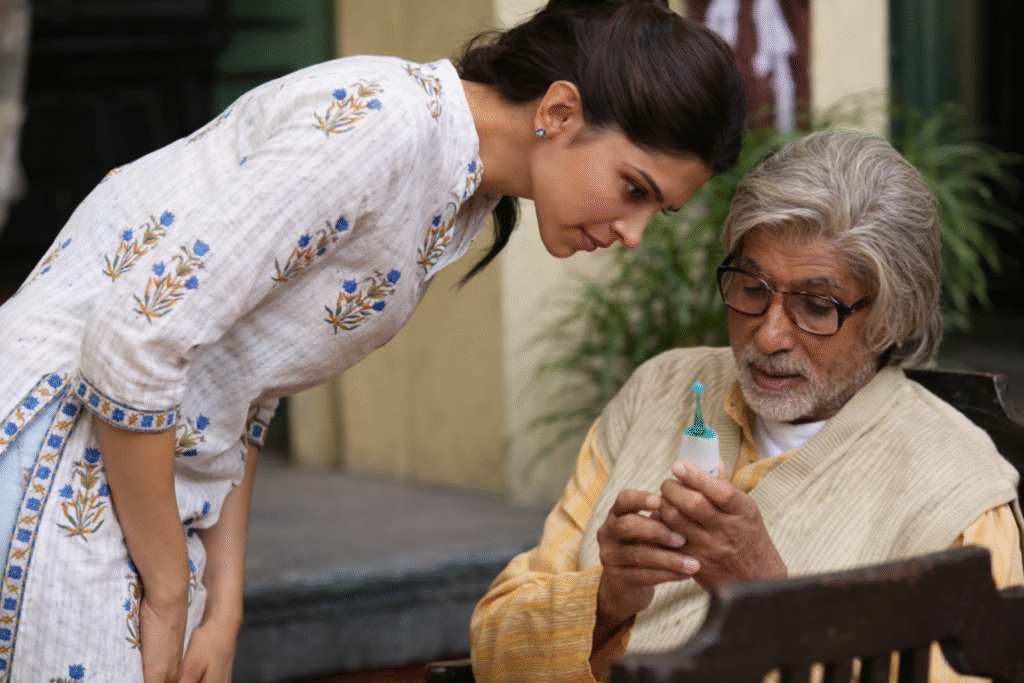

Around this time, Ananya found herself deeply affected by two films, Piku and Dear Zindagi. In Piku, she recognised the constant alertness of managing someone else’s emotional world, and how little space there was to not be responsible. In Dear Zindagi, she saw the exhaustion of holding everything alone and the relief that came when emotional needs were finally spoken. These stories didn’t change her life, but they gave language to something she had been carrying for years.

From an IFS lens, moments like these often create small cracks in a belief system that has held for years. The caretaker part doesn’t step down suddenly, but it begins to notice that responsibility doesn’t have to be the only language of love.

Creating a new Relationship & Healing Without Rejecting Family or Culture

When Ananya came into therapy, the one thing she said she felt relief hearing was

“Healing did not require rejecting her family or her culture. It required gently building a relationship with the caretaker part who believed everything would fall apart if she stopped holding it together.”

Slowly, she began to understand how young this part had been when it first took on its role. How necessary it once was and how loyal it had remained.

Healing did not require rejection or shame and caring did not have to mean self-erasure.

Responsibility did not have to mean constant vigilance. And love did not have to be earned through exhaustion.

Over time, Ananya’s caretaker parts began to soften.

Not because it was forced to step aside, but because it finally felt seen. It started to trust that the present was different from the past.

And of course she still cared deeply for her family but she no longer disappeared in the process.

Do you see yourself in Ananya

If this story feels familiar, there is nothing wrong with you. The part of you that learned to take care of everyone did so to protect connection and safety.

This work isn’t about becoming less devoted. It’s about allowing care to include you too. And sometimes, it begins with a simple question:

“Who would you be if you didn’t have to carry this role anymore?”

Before I close, a small note.

Hi! I’m Sakshi, a Trauma-informed Psychotherapist and the First South Asian Certified Level-2 IFS Therapist, and I write about the inner systems we develop to survive, belong, and stay connected, especially within south asian family contexts from the Internal Family Systems lens.

The story shared above is a composite reflection drawn from recurring themes I encounter in my clinical work along with personal experiences and observation. Any identifying details have been intentionally altered to protect confidentiality, while staying true to the emotional and psychological patterns being explored.